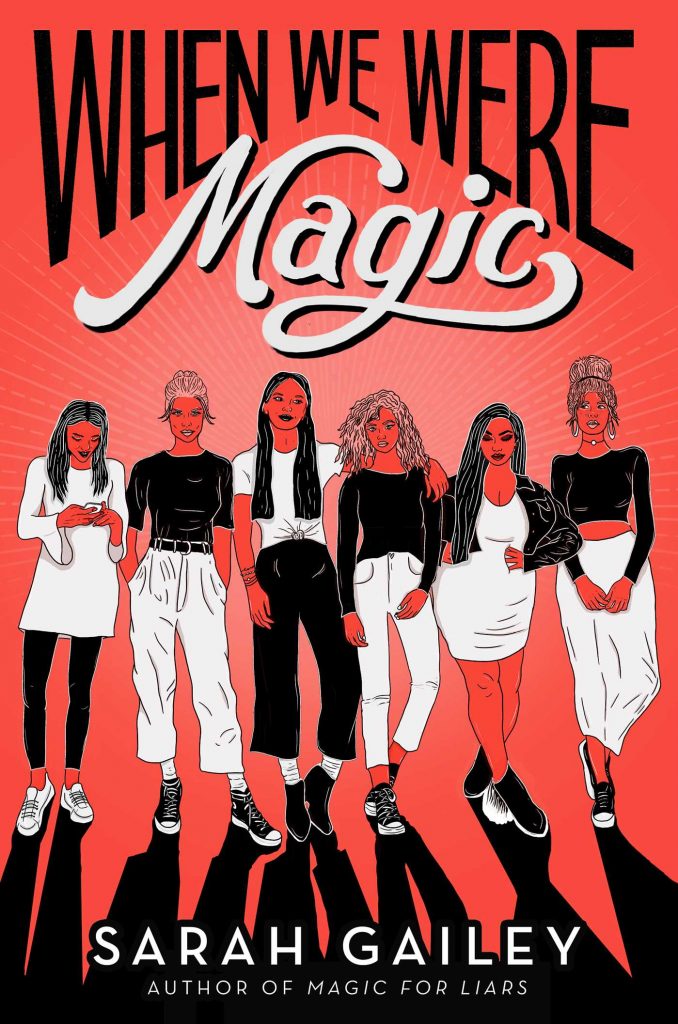

When We Were Magic: Queerness, Witches, and Uncanny Solidarity – Book Review

When We Were Magic by Sarah Gailey, a non-binary author, has just been released. The book delivers on romance, but some of the more… explosive plot elements are left feeling unresolved.

Warning: contains spoilers and discussion of a rather gruesome magical murder and its aftermath.

Reading the blurb on Goodreads for When We Were Magic, I felt my heart leap. Witches and magic, check. A promised f/f relationship with lots of pining and slow-burn, check. A darkly funny twist on a high-school story, check. And all written by a non-binary author.

I felt as though this was going to be it. My 2020 reading was going to peak in early March. I began scattering my to-be-read list to the four winds. What, I thought, would be the point when I had this book to read again and again?

The book I ended up reading when I opened When We Were Magic was – look, in parts, I enjoyed myself. I truly did. At other times, I found I’d given myself a headache from holding a yikes face for too long.

First, some good things. The book dedicates itself “For everyone who isn’t sure yet”, and it does a magnificent job of portraying a main character who is still figuring it all out in terms of sexuality. Alexis has dated a few people before the story begins, boys and girls. Throughout the book, she variously attempts to have sex with a boy she doesn’t really like, kisses a person who is questioning her gender, and has sex with her longtime crush, a girl.

When Alexis comes out to her parents, she describes herself as “not straight”, and mentions to a close friend later that she might be bisexual. Alexis is never pushed by any other character, nor by the narrative itself, into self-identification. Her feelings come first. It’s affirming and well-written.

The author’s talent for description shows throughout the story. The way they describe both magic and romance, in particular, stood out to me as compelling and beautiful.

There is an amount of representation of marginalized groups in When We Were Magic that’s worth talking about. Alexis’ parents are both men. Half of Alexis’ group of friends, who make six altogether, are not white. One of her friends dresses in a way that’s gender-non-conforming and considers using pronouns that aren’t female.

Best of all is the f/f romance that we get. The slow-burn in this one is oh, so sweet. The pining between Alexis and Roya is wonderfully frustrating. If you’re a fan of big chemistry packed into the tiniest of gestures, this is the romance for you. And the eventual culmination of the tension is ferociously and satisfyingly written. My heart ached for the loveliness of them both in the field, with the tree.

The thing is, though, there was a dead boy’s severed arm under that tree. It’s an arm that Alexis and Roya put there. Because it’s from the boy that Alexis murdered by exploding his penis with her magic.

And herein lies the problem for me. How the romance is handled, the representation, the friendships: it’s all so theoretically enjoyable. How the murder itself is handled, though, made me cringe my way through some of the parts of the story I’d have otherwise liked best.

Let me explain. The fact that Alexis and her friends are committed to each other throughout the story is a breath of fresh air. We see a bond of huge depth between at least five women characters and one character who was assigned female at birth and is questioning her gender. All of them are at high-school age. None of them waver in their love for each other as the story progresses.

It should feel miraculous. And yet, with a dead boy in the mix, that’s not the feeling I had as I read.

Alexis’ friends come piling to her rescue at the start of the book, into a room where a boy has recently been brutally murdered by her. Within minutes, some of them are joking over the dead body to try to cheer her up – and yes, perhaps it’s the shock, but there’s no sense of constant underlying tension that makes that explanation feel real. They come off as flippant at best.

And through the book, as the six of them figure out how to dispose of the evidence of Alexis’ crime – burying body parts one at a time – they are variously joking, kissing, and enjoying meeting a coyote while they do it.

No one among the friend group says at any point, ‘this is so, so messed up’, or profoundly acknowledges that they are doing something that could be considered morally horrifying. They handle the boy’s body parts as they bury them without flinching. They never seriously discuss as a group whether they have done anything wrong. The characters are so unfazed by the death itself, but have so much emotional depth elsewhere, that their behavior falls into the uncanny valley. It seems almost human, but just not quite.

And while perhaps this is the dark story I was promised, for me, it doesn’t go dark enough. When something bad happens, the enjoyment for me is in seeing the characters grapple with it. Can they handle what they’ve done? How will they try to make amends? How will they preserve their humanity when it’s under threat from the horrible thing that they’re a part of?

The book doesn’t ask these questions, and its main emotional thrust has nothing to do with the boy who has been killed. Instead, as each of his body parts is separately buried, the friend who buries it loses something. Alexis loses her ability to dream. Roya loses her ability to cry. Iris loses her freckles and her ability to see her magic, and so on.

The angst in the book, Alexis’ uncertainty and guilt, comes from these personal losses, instead of the loss of human life. The friendships are always at the forefront of the book, and ordinarily, I would like that, but in this story, the murder of a boy looms constantly in the background, unspoken and un-dealt with. His shadow makes a triviality of things that should resonate.

As I made headway through the book, I had the sense that the author wanted a murder for the shock factor at the start, but wanted to write the rest of the book about friendship and self-sacrifice and teenage evolution, and not the murder.

The story of six people learning to live with having sacrificed things and changed because of it is one that I would care about and enjoy if they weren’t worried about losing dreams and freckles when a person is dead. The unwavering solidarity between the six friends is something I would adore, if there weren’t a murdered boy’s body parts split between them while they joke and make out and never, ever address what they’ve done to the boy and his friends and his family in a meaningful way.

I kept waiting for someone to shriek, “But he’s dead! He’s dead, and you killed him! So, no, we can’t just sit and eat French fries and burritos like we normally do! He’s dead!” There was one character who seemed as though she might be the kind to do just that, and then she was cursed to be unable to speak about anything she knew. By the end, she was hooking up with one of the six friends. The realism of the character choices starts to feel below zero because of the enormity of the thing they’re not being allowed by the story to acknowledge.

One of the author’s core messages in the book is also shifted by the way the killing is treated.

When Alexis doubts her friendships, and feels like a burden, her angst is relatable. When her close friends reassure her and even lecture her about how she should trust them to take her weight if she falls, it’s important messaging in a YA book. But it’s all in the context of something that is just too horrible.

Alexis, you should stop apologizing and just let yourself be grateful instead is a wholesome message, but it’s one that feels shudder-worthy in context. A boy has been bloodily killed and Alexis is encouraged to be grateful to her friends for helping, rather than feeling guilty for making them help. Her guilt over having killed a person is not often mentioned and has little to no bearing on her actions. The boy’s parents are mentioned in passing as grieving their son with cheap flowers as his classmates graduate high school. Alexis doesn’t cry, because after all she didn’t know him very well.

In fact, Alexis laments throughout the book that she didn’t know the murdered boy as well as she should have done, and then she does nothing to learn about him whatsoever. She makes no effort to make amends on this front. We might excuse her actions by saying she thinks for most of the book that there was a chance he could be brought back; once that hope is taken away, nothing changes, however.

For what she did – used another person, murdered him without dignity, never gave his parents any explanation to help their healing, and never apparently learned enough about him to shed a single tear over him being missing from the graduation ceremony – for all that, the worst of Alexis’ consequences is losing her ability to dream. And the one thing she says she misses dreaming about most is being with Roya, which is something she can do in real life by the end of the book, anyway.

Alexis comes out of the story with everything she wanted, thinking more highly of herself than before, and a person is still dead. And it doesn’t seem to matter.

I wanted the murder in this story to have impact. I wanted it to be felt all the way through these characters, for it to shake each one of them differently. In the end, the story veered close to villainous queer tropes at times as the friends ignored the consequences of what they’d done to the people close to the murdered boy, and disposed of body parts without any apparent qualms.

It’s not that I think it’s unrealistic for a group of people to have a warped sense of morality after having done something heinous and to bolster each other up through having done it. But any interesting angle on that was ironed out by how clearly I was supposed to like all of these six people. How much I was supposed to be learning about not needing to feel guilty. How sincere and unfunny this book is, at its core.

It’s like trying to watch an episode of My Little Pony set inside an episode of, say, Game of Thrones. Yes, this story is absolutely trying to teach very important things, and yes, friendship is magic, but someone has died bloodily and cruelly and far too young, right there in the background – and for any of the story to resonate, that needs to matter.

I wanted to like When We Were Magic. I still do feel positively towards it in many ways. Despite my reservations about the plot, I’d recommend reading it if you’re a fan of a slow-burn romance. But if you need me, I’ll be out asking the four winds for my to-be-read list back.

(Or maybe you can just check out the books tag here on the Geekiary, which is full of reviews and recommendations.)

Author: Em Rowntree

I’m a non-binary writer, teacher, and cat-lover from the UK.

Help support independent journalism. Subscribe to our Patreon.

Copyright © The Geekiary

Do not copy our content in whole to other websites. If you are reading this anywhere besides TheGeekiary.com, it has been stolen.Read our