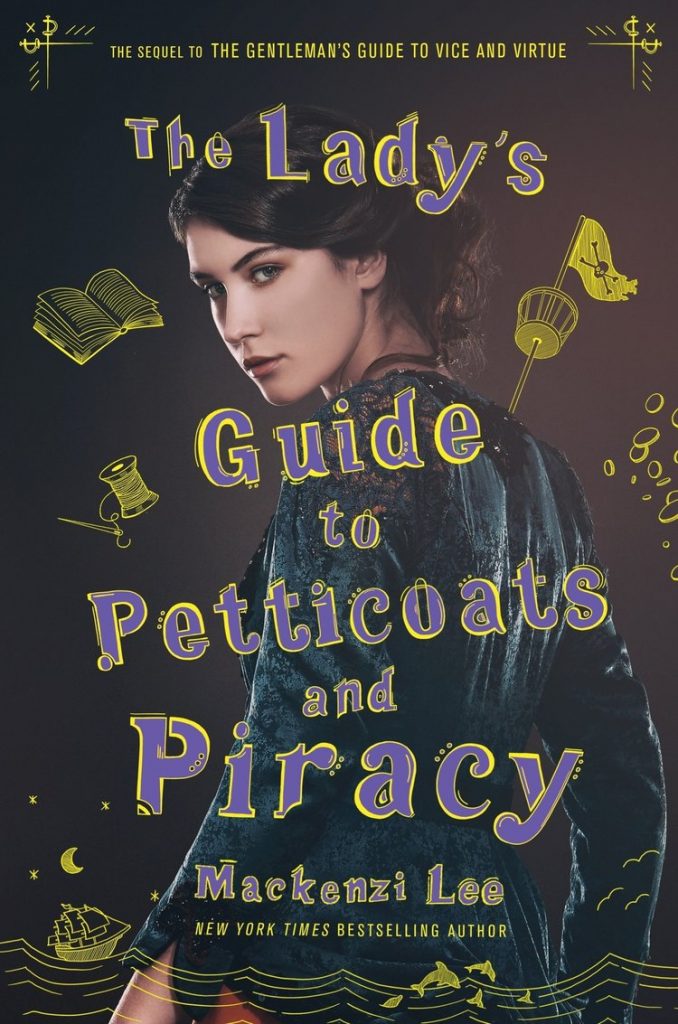

“The Lady’s Guide to Petticoats and Piracy” Has the Asexual/Aromantic Character You’ve Been Looking For

Asexuality and aromanticism are two orientations that rarely catch a glimpse of the spotlight on the stage of representation. It’s a common belief that a story without some form of sex or romance at its core wouldn’t be much of a story at all, and certainly wouldn’t sell. The Lady’s Guide to Petticoats and Piracy takes this misconception by the horns and stops it in its tracks.

The Lady’s Guide To Petticoats And Piracy weaves together a gripping tale of a woman in eighteenth-century Europe doing whatever it takes to become the licensed physician she’s always dreamed of becoming. Felicity Montague’s ambitions takes her on a daring adventure full of scheming, mystery, and piracy. That in and of itself has the makings of being an excellent story, but the reader gets to experience an extra dynamic as they also watch her turn down suitors, run from marriage proposals, and struggle over what’s expected of her versus what she truly wants.

The book, written by Mackenzi Lee, is the second in what’s being called “The Montague Sibling Duology”. While Felicity’s orientations were hinted at during The Gentleman’s Guide to Vice and Virtue, they’ve now taken center stage in her very own story as confirmed by the author.

At first the internal struggles that drive the story seem to be mostly of an eighteenth-century nature, but the author still manages to make them incredibly relevant to the struggles of asexual and aromantic people of today.

- A well-meaning comment about how they hope she’ll find someone to love one day

- A dismissive statement on how she just needs to find the right person

- Trying to untangle feelings of not wanting to be alone, but not wanting the antidote to be found in marriage

- The feeling that it might just be easier to cave into societal norms

These things – and more – are timeless problems for the aro/ace community, whether it’s the eighteenth century, or the twenty-first.

Felicity doesn’t begin her story confident in her feelings about love and relationships, and even has moments of experimentation. Over the course of the two book series, she shares kisses with two men and one woman, and each time remains unimpressed by the act and ultimately decides it provides no magic for her and is “just a thing people do”.

It’s also pointed out that Felicity, along with every other asexual or aromantic person, does not need to try out kissing or sex in order to know whether or not it’s something that she’s missing out on – something that is very relevant for people of today to understand as well. Some people do experiment, and some don’t need or want to. Every exploration into figuring out who you are is a valid one, and no two are exactly alike.

Felicity’s journey is one that I recognize in myself as we both came to the same eventual conclusion during the course of our lives : romantic and sexual relationships might make some people happy, but we are not some of those people.

The Lady’s Guide To Petticoats and Piracy is an excellent example of an interesting and dynamic story that is also free of a romantic subplot for the main character. Instead, Felicity explores the concepts of race, gender-equality, what it means to be feminine, and how to carve out a place for yourself in a world that resists the chisel.

And piracy, of course.

If you are as desperate as I am for some good asexual and aromantic representation, I’d tell you to look no further than Felicity Montague, but please do continue to look further and wider for any more well-written asexual or aromantic characters.

We’ll always be in need of more.

The Lady’s Guide to Petticoats and Piracy by Mackenzi Lee is published by Katherine Tegen Books and is currently available wherever books are sold.

Author: Michaela Labit

Help support independent journalism. Subscribe to our Patreon.

Copyright © The Geekiary

Do not copy our content in whole to other websites. If you are reading this anywhere besides TheGeekiary.com, it has been stolen.Read our

While I don’t think it’s very difficult to find books without (much of) a romantic subplot, at least in the fantasy / scifi / mystery genres (which I stick to for this very reason), this book does sound particularly interesting. I’ll definetely will be checking it out!

You’re right, it is still extremely rare to find books with ace and/or aro characters, especially if you’re like me and not interested in reading books where romance is the main plot.

Then again, that sometimes makes it easier to find books where you can comfortably identify with the protagonist, because the author just wasn’t interested in writing about romance or sex – e.g., like with the original Sherlock Holmes stories. Or with large parts of the Discworld series – even when there is supposed to be a romantic subplot, it’s written so perfunctory and almost like a parody from someone who doesn’t like romance plots, so that I sometimes really think dear Sir Terry must have been playing for our team. Especially his author avatar, the old witch Esme Weatherwax comes across as aro-ace, even if that was originally just a character trait to make her contrast against her friend, a cheerfully promiscuous mother of a dozen sons, the equally old witch Nanny Ogg.

Terry Pratchett wasn’t good with explicit queer representation, though. One of the later books, where he actively tried, and which can be read in isolation, is “Monstrous Regiment”. (It ties in with the Watch novels, but the characters from those novels mainly just show up as a deus ex machina in the end to keep things from ending in tragedy. The primary characters and setting of this novel don’t overlap with the rest of the Discworld canon. This book, while still humorous, is also a good deal darker than most of the other Discworld novels, due to the themes of war and deeply mysogynist culture.) Among the main characters there’s a lesbian couple and one or two characters who I would think were meant to be read as genderqueer if I could be sure Sir Terry knew what “genderqueer” means. (SPOILER:

Almost all the major characters are girls and other afab people who pretend to be male to join the army. But one character has spent almost her entire long life that way, and is far more comfortable in the male persona by now; and the other also stands out for being very at ease while presenting as male and he/she only comes out to the others very belatedly, when a girl he/she seems to have a crush on remarks on the beauty/feminity of another woman – so it comes across like the genderqueer character was trying to say “You like girls now? I have boobs, too, under this uniform!”

SPOILER END.)

This book is one of the Discworld novels that don’t have a romantic subplot at all, so the characters’ sexualities don’t really come up much. The reason I recommend it here is the main protagonist Polly, who for some not explained reason is absolutely sure that she’ll never marry (granted, most of the young men of her country are dead, but there are some disabled veterans and her inheritance of a prosperous tavern would make her a very attractive marriage prospect for these men who are no longer able to earn a living by farming); she doesn’t ever show a positive attitude towards or about any male other than affection for her mentally disabled brother (and she only ever makes one positive comment about a man’s looks – good teeth – …right before kicking him in the groin because he’s a privileged asshole); but at the same time, her reaction to the above mentioned lesbian couple reads like the idea that girls can be attracted to each other also never entered her mind before. So, she’s not explicitly labeled as asexual (bit hard to do in a quasi-19th-century setting), but you can make a strong case that she is.

Another recommendation would be the Jacob’s Ladder trilogy by Elizabeth Bear (“Dust”, “Chill”, “Grail”), which are transhuman / lost generation ship type sci-fi by genre, but at least the first novel is narrated like a classic Arthurian questing adventure (i.e. the characters think and behave like they’re in a quasi-medieval high fantasy setting, the various computer A.I.s are referred to as angels, the radioactive coolant leak is described as a mythic monster, etc.). There are quite a lot of queer characters (lesbian, bi/pansexual, genderqueer) and the secondary protagonist (who becomes the primary proagonist in the second and third book) is Sir Perceval, an explicitly asexual (“asexed”) young female knight who has a romance plotline with the more-or-less lesbian protagonist of the first book. (“More-or-less” because she has a sex scene with a genderqueer / voluntarily intersex character who offers to get rid of their penis for the encounter, but she tells them that it’s okay. That genderqueer character later has a romantic relationship with a male character who previously thought he was straight, too. So sexuality is generally treated as fairly fluid in these books.)

Elizabeth Bear’s stronger points are plot, unique world-building and political concepts (in this case social darwinism / libertarianism and Christian extremism turning into feudalist oppression VS. as-humane-as-possible but extremely anti-religious democratic communism), not so much very engaging characters, so memorable characterization isn’t really where these books shine. And Perceval’s asexuality is not closely examined – it’s just there and that means that the romance is not going to be consumated even though the characters are in love and want to stay together, and that’s that. Besides, it goes along well with the whole Arthurian theme that Sir Perceval has taken a vow of celibacy. And SPOILER:

I fear it originally was just included to take the squick out of the romance plotline in the first book, because it eventually turns out that the two young lovers are half-sisters. So it seems like this romance is presented as okay because nothing sexual is ever going to happen between them, not because they didn’t grow up together so there is no problem of power-abuse or grooming. And then the lesbian protagonist makes a heroic sacrifice and the issue becomes moot anyway. (This feels less like “bury your gays” because there are several other queer characters. But a lesbian reader may feel otherwise.)

SPOILER END.

Still, it’s one of the very few books I’ve ever read where there is an asexual major character but that asexuality isn’t presented as a huge issue and source of angst that consumes the entire plot. The plot here is mostly about something other than romance, so the asexualiy feels more naturally integrated, just one facet of the character and far from their main problem in life.