Pulga Escapista Wants to Capture Argentine Folklore – Interview with Julián Vecchione

It’s natural to think of games as a product of culture. As man-made artifacts, they are in conversation with every line of implicit and explicit text that a zeitgeist has floating around.

Last time we talked about El 39, and its desire to reflect the quotidian misadventures of young folk in Buenos Aires. But culture is more than just quotidian anecdotes. As important as those are, the image isn’t really complete without a good dose of folklore.

Being as vast and diverse as it is, it’s no surprise that Argentina has amassed quite a varied array of creatures and tall tales. A complex mixture of indigenous tales and countryfolk superstitions gives birth to a post-colonial concoction with never-ending potential.

Cazadora, by Pulga Escapista (which you could translate as “Escapist Flee”), is a 2D action game where you play as a huntress who tracks down various creatures from Argentine folklore. Needless to say, it all ends up pretty bloody.

I got the chance to talk with Julián Vecchione, the lead designer, and I can’t deny that he has quite the remarkable profile.

Julián Vecchione describes himself as “a Recreation and Leisure Technician.” He’s dedicated all aspects of his life to making games for quite a long time now. He shared that what he does the most, “what puts food on the table,” is that he’s also a board games publisher. He designs, edits, and publishes board games from other authors as well as his own.

“But all with the same editorial seal that is Pulga Escapista. For a while, I’ve also occasionally done role-playing games. More as a hobby, but I design them in PDF.”

He added, “I’m also trying to transform it into a videogame studio of sorts. Cazadora is sort of the principal project. We’ve done some games from jams, more in a recreational way, let’s say. But Cazadora is like the first professional project.”

“I’m playing the role of game designer and a project manager or producer of sorts. Whatever you want to call it. But yes, (…) the majority of my time I’m either playing, or thinking about games, or making stuff related to production.”

Furthermore, Vecchione also gives classes about board game design and such. Whatever he does, he tends to always deal with game-related stuff.

All in all, Vecchione has been making games for 8 or 9 years, 5 out of those professionally. With such a pedigree, I couldn’t resist asking him about his favorite game designers.

“Well, yes, there are a lot. But trying to keep it short,” he answered. “When it comes to board games, Reiner Knizia is a designer who inspires me a lot. He’s a very prolific German designer with more than 800 published games. He has such a mathematical analysis. The guy has a PhD in Math, precisely. He has a very deep analysis on the math part of games that I love.”

“Then, when it comes to roleplaying games, I follow and read and get inspired a lot by Vincent Baker. It’s an indie game author that’s very cool.”

“And with regards to videogames (…) lately I’ve been increasingly impressed with everything behind Hollow Knight. I think what the people of Team Cherry did is tremendous. It’s a great game in all aspects. I find it really inspiring.”

“The worldbuilding, the art, the gameplay… everything. I think it’s an example of so many things.”

Naturally, since Hollow Knight also has 2D fighting, I wanted to know if there was some DNA there.

“There is something. Maybe it isn’t a direct inspiration. But, there’s a certain feeling. I think we are going for something more like… maybe Blasphemous. (…) The character is heavier and has less mobility, let’s say. It has a slower focus.”

By this point, it is clear that Vecchione knows his stuff. Nevertheless, Cazadora is the fruit of the collaborative work of many people, and I wanted to know more about the team.

“Yes, the team has been mutating. Right now we are somewhat big, seven people. I do the game design and production. Then there are the programmers, who are three: Luciano, Juan Pablo, and Manuel,” shared Vecchione. “And then… The artists. Javier, Ignacio y Alejo. They manage all the visuals, animation, and such.”

“And you could say that there’s an eighth member, that isn’t fixed, but contributes. It’s Martín, who occasionally sends us music and sound effect assets. He isn’t fixed in the team, but rather works as a sort of freelancer. Let’s say. It’s voluntary work, but he does the assets when he’s able to.”

I asked him if they had worked together before.

“The majority of them I knew from other projects, and I invited them to this one. And some of them, once we started the project with the core team, let’s say, we searched online. If people we knew or had a reference for wanted in too.” He added, “Always under the fact that our budget is currently zero. So it had to be people with an interest in the project. With the availability to get into a project that, at least for now, doesn’t produce any income.”

“It’s bound to the time that each one can do. We try to put a fixed number of hours in each week.”

It’s a very hobbyist endeavor, then. But Vecchione and the team have hopes of going professional with their work on Cazadora.

“We’ve been debating that a lot as a team. It started as a hobbyist project, but it’s mutating into something professional. I think that getting into MPVP made us realize that the game has potential and that people are seeing it.”

Mi Primer Videojuego Profesional (“My first professional videogame”, abbreviated MPVP) is a project by the Argentine Game Developer Association (ADVA in Spanish) for mentoring upcoming games.

Each year, they select just a few candidates, and the few winners get special mentorship along with a guaranteed space at EVA (Argentine Videogame Exposition), the biggest game development event in Argentina.

“Today, our objective is very centered on the EVA. To sell, get a publisher, thanks to the EVA, the business talks, the visibility it all generates. Sell the game to a publisher and get to work with a budget to finish the game. With all that it entails,” said Vecchione.

The mentorship and counsel have been really valuable for Vecchione, and many months after entering MPVP, Pulga Escapista presented Cazadora at Indie Dev Argentina.

“It was wonderful. It was great to know that we got in, because there were more than a hundred submissions and only 20 were selected, I think. That was a big recognition already. Then we got nominated as best Argentine representation, and that also felt like a great acknowledgment.”

He continued, “And the event itself was a great testing opportunity. We’ve had tests before, but in two days, we got around 125 people to play the game, which is a lot. It gave us a lot of feedback, both verbal and through observing them play and react. If they were comfortable, if they understood the user interface, and if not, why not?”

“We got a lot of first-hand info. And also lots of people from the industry approached us. We got contacts, the chance of consulting people, and doing interviews like this one. We also got to talk about participating in streams. I don’t know, a lot of things happened because we were there. Physically at the place and sharing with the community.”

Having quenched my curiosity about Vecchione and the team, I shifted the focus to Cazadora and its concept. How did it come to be?

“I always had a personal interest in mythology and folklore in general, from a very young age. When I was young, it was mostly about foreign mythos, like Greek mythology and such,” Vecchione replied. “As I grew up, mostly during my adolescence, I found out that there was a lot of Latin American culture that was super interesting, related to saints, monsters, various myths that didn’t have a lot of representation outside the country.”

“But even inside the country, they were left aside, with the logic of a cultural globalization of sorts.”

“I started interiorizing that and I said to myself that it would be wonderful to tell these stories and prevent them from being confined to old people and indigenous folk. Giving them the chance of having a bigger generational impact.”

“And I started to get this idea of, well. Why not an action game where these creatures are the protagonist, or rather, antagonists? But they have the focus, a major role, and we get to know these legends. Not just reading a book, but rather being immersed in that world, that aesthetic, that logic.”

“And also bringing back something of the gauchesco, certain literary and musical genres. The game also has Martín, that’s the composer, and he is a folklorist (note: “folklore” is the term used for what you’d call Argentine country music).”

“Doing something with the musical and literary Latin genres, Argentine genres. Taking them to the presentation and the screen, right? And it’s from there that the concept arises, and we’ve been developing it from there.”

Argentina is a pretty big place, however. Many different traditions and tales depend on where you are at a given time. Would Cazadora be confined to a specific region, or explore a bigger selection of folklore?

“The focus is pretty general. The goal is that when the game is finished, each level is a different province. And the monster, the ambiance, and logic are all related to that specific province,” Vecchione responded. “Today, what we have in the build is in Misiones, and focuses on a creature called the Guazú, which is an Aguará Guazu that stands on two legs, and it works as a lobizón (note: a sort of werewolf.)”

“(…) But we have conceptualized nine levels. Each one in a different province, with its monsters and idiosyncrasies, let’s say.”

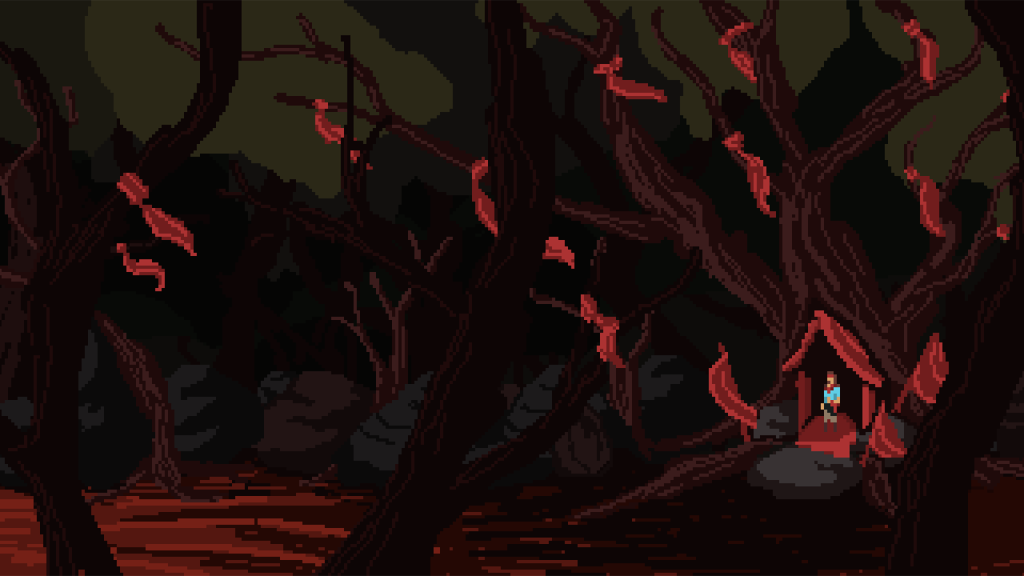

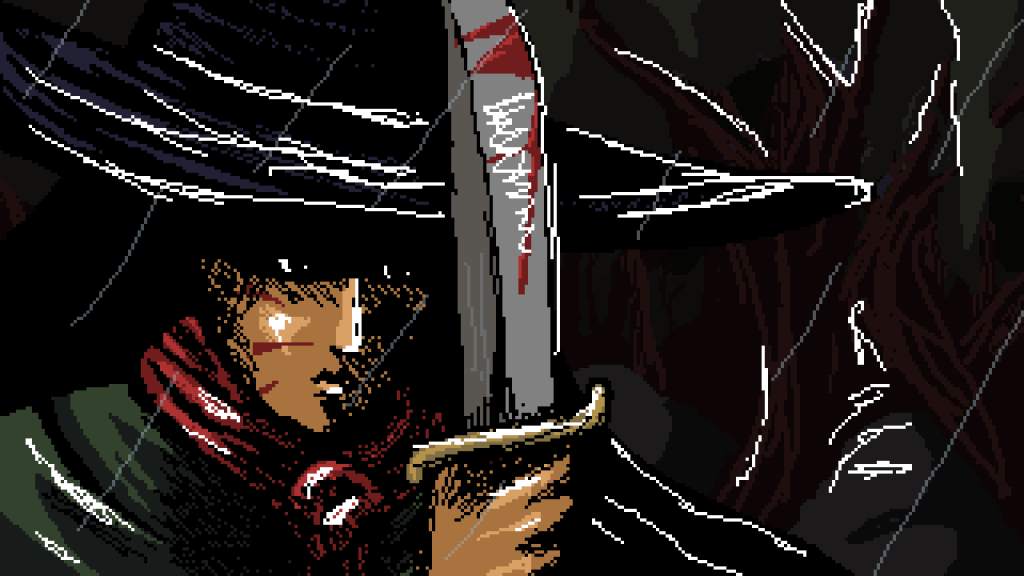

One of the most striking aspects of the game is the careful use of visuals, combining darkness with a certain palette to create very moody scenes. I asked Julián about the process of arriving at such a style.

“Yes, the first phase of the project was long and related to that. It started with an artist, Pedro Cavalchini, that you may know from Tenebris Somnia (…). He’s not working with us anymore, although sometimes he collaborates a bit.”

“He did all the initial concept art, let’s say. Drafts and such. We identified a logic of what we wanted and had a challenge in depicting the epic aspects of the game, and such, with pixel art.”

“Pedro gave us many ideas, we worked on them a lot, and we got to a logic we liked. Then he, for various reasons, stopped working on the project, but he laid the foundations.”

He added, “Then followed the current lead artist of the game, Javier Etcheverry, who added his logic. He darkened the game a bit, which went very well. The game got a darker palette of night-tones. Blacks, reds, browns… it gave it something, without being horror (…), it gave it that darkness that I’d describe as dark fantasy, let’s say. I think it added a lot to the aesthetic and palette of the game.”

I asked Vecchione if the game was intended for the global market or if it was meant to be something more local, given its deep cultural roots in the country.

“Our idea from the beginning was for the game to be a cultural export. A product with Argentine and Latin American identity, but that’s possible to consume coming from other markets. My logic always is that we as Argentineans (…) can play, for example, The Witcher without knowing all the culture that is behind, but getting to learn it along with the game.”

“Or Blasphemous, even. You don’t need to know the Spanish Christian logic to play Blasphemous, but you get to explore it in the game,” he continued. “So the invitation here is the same. You don’t need to know Argentine and Latin American myths, it’s enough that the game hooks you through aesthetics, music, and such, so you want to explore and get to know more through the game.”

“(…) The idea is to generate an exotic curiosity. And get to show our culture, which I think can be really interesting.”

The game is, then, deeply rooted in culture and has great ambitions to bring local imagery to new audiences.

Female protagonists have been part of games for a long time now, and in that context, it isn’t weird to see that Cazadora‘s titular protagonist is, in fact, a woman. Regardless, I wanted to get Julián’s take on such a choice for the main character.

“From the very start, it was always a female hunter [note: “Cazadora” translates to “female hunter or huntress”]. The game was always called Cazadora. It was always part of the idea matrix, I think. To me, there’s a message there, of who gets to be a protagonist in a game.”

“And it also has to do with the game’s story. (…) The huntress, during her childhood, a monster steals her voice. Then, during the adventure, she’s a mute protagonist trying to get her voice back. The story has a lot to do with the huntress’ history.”

“It also has to do with the role of the huntress in society, and overall, thinking that the game is set not in modern times, but rather around the start of the 20th Century. (…) It’s not the regular protagonist of a game. It happened a lot at IDA that they thought she was a gaucho. They referred to her in masculine terms. And just when the demo stops and you can see the cinematic, they realize that, wait, no, it’s a woman. It’s weird. There was a surprise, I don’t know if positive or negative, but there was surprise.”

He shared, “I find playing with that surprise and subversion interesting.”

I couldn’t help but notice that 20th-century Argentina had a very volatile social and political climate. How much of this environment was Cazadora aiming to capture?

“The focus is undoubtedly much more centered on the mythological. But there are elements of social conflict, too.”

“Just today we were doing some early revisions, and there is a level we’re thinking through with a creature called The Familiar, that lurks around the northern parts of the country. We’re telling the story of this demonic dog that answers to the masters of a sugar plantation, and they use it to discipline their employees who ‘misbehave’, don’t follow the rules, and such. And there’s something there of a social conflict of that era, in which workers were really exploited and masters treated them really badly. The idea is capturing a bit of that.”

“(…) precisely at some point in mythos in general, in every culture around the world. What do we decide to call a monster? It’s what we see as morally wrong. And we want to question that in the game. What is bad? Who occupies that role?”

“And at what point a person can’t be worse than a monster, too.”

Returning to the game, I asked Vecchione how he envisioned the full gameplay loop.

“Well, it’s a 2D pixel art game, an action game. Focused on that, and we lately use the label Boss Rush a lot. The game is flowing in that direction. We removed things that didn’t have to do with boss fights.”

“You have a contract that sends you to a particular province. You go there, find the monster, and get to fight it. Before each fight, you always get to meet a saint, who, depending on the zone, can be the Gauchito Gil, the Difunta Correa, or San La Muerte.”

“Each of these will let you choose some kind of power-up that helps you during the fight. (…) But the focus is the fights, 90% of the time, you’re gonna be fighting. It’s not a game where there are lots of enemies on the screen.”

“It’s a boss per screen, and each boss is unique. So it’s a boss rush where there is a build-up before the encounter, and an upgrade screen. It’s a very different atmosphere, but you could compare it to Cuphead or Furi, where the focus is on the boss fights.”

Such a focus on boss fights screams for a good parry mechanic, but Cazadora decides instead to focus on movement and quick thinking. What led them to such a choice?

“We debated it a lot internally. There was a proto-parry on early versions, and the game revolved around the timings with that,” Vecchione shared. “We ended up realizing that we wanted to make the player feel like a human being against a bigger, stronger monster. And the parry was giving a feel of equal standing, almost like fencing. We felt like avoiding the hits would better convey the fact that this monster really can destroy you. (…) There’s a deliberate choice on the short range or your knife, too. You need to keep a distance from the monster’s attacks while having to avoid staying near for too long.”

“We’re still considering doing something else. Not like a parry, but like an incentive to move following certain timing and such.”

I asked Vecchione what would be the thing he’d like to add if he could, scope and budget be damned.

“We’re focusing a lot on the upgrades now. It’s something that interests me a lot because it gives customization to the experience. I’d like for each upgrade to change a bit of the strategy and gameplay.”

“And also that they reinforce each saint’s identity thematically. Gauchito Gil representing bravery, la Difunta Correa representing healing and empathy, and San La Muerte embodying something darker, like vengeance.”

“All those aspects are really important for the story and its character. The idea is to have 18 upgrades, two per currently planned level. You’d be seeing 50% of the upgrade per complete playthrough. We want to make a post-game where you’d have more freedom with the upgrade tree and with some changed aspects to the fights.”

“I don’t want to spoil, but something happens at the end of the game that justifies a bit the fact that you get to go through it again with harder enemies.”

Was there any province that he enjoyed the most when it came to design?

“Lately, I’ve been obsessed with the end of the game, which happens in Buenos Aires. It exists in the rural context of the rest of the game, and you end up in a city with tango playing and a type of dynamic that I think players will like a lot.”

When it comes to depicting Argentina, getting to Buenos Aires was kind of inevitable.

“Yes, it’s a very important point and culture. To me, it was important for it to be at the end, and that you first get to go around the country. You go through eight or nine provinces before finally arriving in Buenos Aires.”

Closing our interview, I wanted to know what Pulga Escapista had in store for the future.

“Our plan right now is EVA. As part of MPVP, we have a stand at the event guaranteed, and we want to take advantage of it to the fullest. Not only the stand but also the business round and everything that happens around EVA. We want to get there with a complete vertical slice, with a good feel and all the features we want to add. And from there, try to get a publisher, develop the whole game in one or two years.”

He added, “We have some ideas for DLCs and other kinds of content to keep it alive and adding more to the experience. So that’d be our plan. (…) If we don’t get a publisher, we would plan to leave a very polished demo on itch. We wouldn’t self-publish because it would take us time, money, and knowledge that we don’t think we have today.”

It was hard not to ask Vecchione, being so dedicated to the craft, if more game ideas were floating around in his head.

“Yes. I’ve got plenty. It’s not my main job, so I’m focusing only on Cazadora at the moment, but there are always notebooks full of notes and other games that might emerge. Lately, we’ve been thinking about a spin-off of Cazadora about a character that appears in the game. There’s a lot of material, and I get carried away and get a lot of ideas. But well, it’s one step at a time.”

–

- Check Pulga Escapista’s socials.

- Check Cazadora‘s demo on Itch.

- See more of our event coverage.

Author: Claribel M

Writer, narrative designer, journalist. Perpetually doing too much.Help support independent journalism. Subscribe to our Patreon.

Copyright © The Geekiary

Do not copy our content in whole to other websites. If you are reading this anywhere besides TheGeekiary.com, it has been stolen.Read our